This story is part of the Niles West News 2025 Immigration Series which documents community members’ experiences immigrating to the United States. Most of these stories are written by Niles West News writers, but some will feature guest writers who will tell their family’s story.

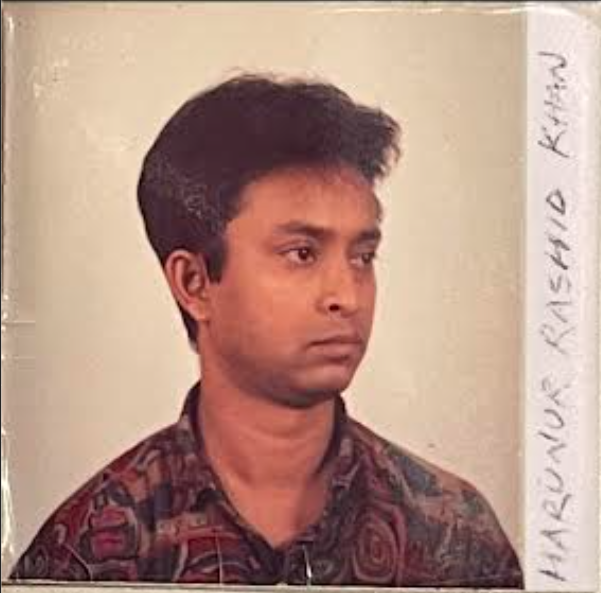

My father Harunur Rashid Kahn immigrated to the US in 1991. He did so with $1,600 in his bank account, basic English skills and a management degree, a degree that no longer carried the same weight in America. He left his home, family and everything he ever knew for a chance at a better future. A future that would give him more choices and freedoms than he had ever known.

In truth, my father told me, he had never actually intended to immigrate to America. It all started out as a game. He and his friends had always been a rambunctious group. Often playing sports together and skipping school to smoke and hang out. On one of these evenings, the group had heard about the Diversity Visa lottery from a local newspaper and decided to enter just to see what would happen. My father remembers that the next day he was sitting with his mother, my dadamonie, and a news report came on.

Telling them about the first winner, a Pakistani man, he vividly remembers what he said next: “I’m going to win next, you’ll see my face up on that screen tomorrow.”

At the time it was a light-hearted joke, but now my father recalls it with startling clarity because it was the first time he got a hint that his life was changing course due to divine intervention. My father remembers the day after too.

He remembers leaning up against a tree after praying in the local mosque. He remembers straightening his spine and ending the “chit chat” when he saw his father approaching on a rickshaw.

“A son always had a certain respect and distance from their father. It’s not like it is here in the U.S. You aren’t friends with your parents. You don’t often joke, chitchat or spend time with your father because he is not your equal, he is superior to you, so keeping your distance is a sign of respect,” Khan said.

My father started to say goodbye to his friends and walk back home when his father shouted at him to join the rickshaw. As soon as he hopped on he could tell that his father had big news to share because he had come home from a business trip early. My father’s family moved around quite a bit due to the government job of my grandfather, my dadabhai. My father used his cousin’s home in Chittagong as his mailing address, and when my dadabhai went on his trip he stopped by and found a letter waiting for him.

“You’re moving to America, you won that lottery, and now you’re moving,” my grandfather said, not a question. A statement.

My father says that when he learned the news he felt “like the world was slipping away.” He also questioned why his father was so determined to see his son immigrate. But I believe I understand.

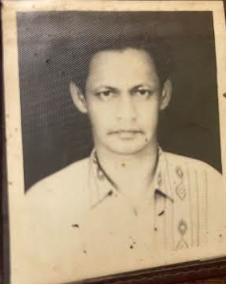

My dadabhai was an intelligent man. He grew up in an improvised village named Noakhali as the son of a teacher. He went to England and received a degree in engineering, to some it might not seem like a major feat, but let me remind you, the percentage of people who were literate in 1950s Bangladesh was 17.6%. In 1952 my fourteen-year-old grandmother married a 21-year-old man, a man who then left to receive an education abroad. He missed the birth of my father; though I don’t claim to know what was going through my grandfather’s head, I do think he was sorry to miss the birth of his first child. I also think he was terrified, terrified that he would lose his chance at college, that he would be beaten out by someone who didn’t have a young family on his shoulders.

Eventually, he was forced to come back after his final year of college, though he wanted to stay to receive higher education. My grandfather eventually rose out of the village and received a prestigious position in the governmental initiative to build railroads, but I think that he resented the missed opportunities in his life, the thirst for knowledge he was never able to quench, due to family burdens. That’s why I think my grandfather pushed my father to move. To give him a chance to better his life, and have more choices, a chance my dadbia never got. My father took it because deep down inside I think he knew he wanted to do the same for his children.

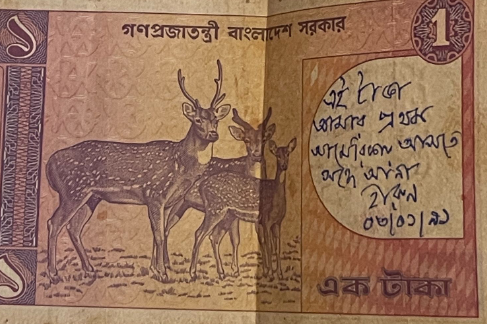

When my father left for America, my dadamonie packed his luggage to the brim with sweaters and forced him to eat double his usual servings, because in America he would surely starve. With this in mind, my father’s first instinct after getting off the plane was to find somewhere to eat. “I just saw these beautiful golden arches and knew I was in the right place,” my father said. That place was none other than McDonald’s. There my father had the best meal he had ever eaten, a McChicken, fries, and a Coke. At that McDonalds, he took out a one taka note and wrote “Today is my first day in America” and the date.

My father chose to attend South Illinois University, he lived with four other guys in a small apartment near the school. They all split chores and groceries, shared a small rice cooker and ate off cheap plastic plates. Even though he was always surrounded by people at all times my father was eternally lonely. He missed messing around with his friends, speaking his language, and spending time with his family. My dad had trouble understanding and communicating with the people around him, which made looking for a job extremely difficult. He didn’t understand the term “looking for a job,” because to him looking meant physically looking, so why would you be “looking for a job,” since it’s not a physical thing? He eventually found one as a waiter, and then a front desk worker in a Renaissance Hotel, but he loneliness ate up at him. My father eventually decided it was time to marry.

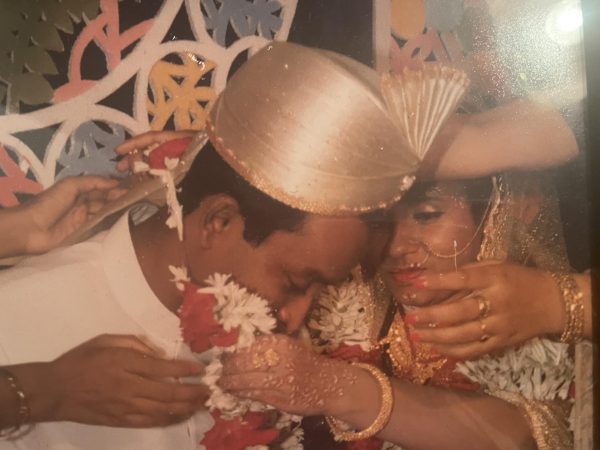

My parents, like many couples in Bangladesh, were arranged. Their families met through my mother’s sister who heard about my father’s marriage offer. My mother, Sabina Ara Begum, told me that she was originally going to marry a doctor, but she rejected his proposal when he refused to shave his beard. My father now has a beard. Fortunately for him, he did not when they first met. They took a liking to each other and got married in 1996.

Their backgrounds were starkly different and that is clearly demonstrated in their first memories. My mother’s first memories were of watching Tarzan and evading her tutors. My father’s first memories were of seeing dead bodies in wells because my father is actually older than the country he is from. He witnessed Bangladesh’s independence. Bangladesh is 53 and my father is 57. He remembers hiding from planes in fear of bombs dropping on his head. He remembers running in the middle of the night to a train that would take him deeper into Bangladesh territory. While my mother’s family was privileged enough not to be truly affected by the war my father’s family suffered, because they did not have the protection being a part of upper-class society provided. In means of status, my mother was out of my father’s league. Here was the beautiful thing, my father was American now. He held an elite key to America, which was far more valuable than land or wealth.

My mother remembers why America was so appealing to her and many other people in Bangladesh.

“Everyone wanted to go to America because it was seen as the pinnacle of the world. We had all grown up on American movies and culture, so we were all accustomed to thinking America was the highest place to go. So when your father [Khan] came with his proposal, my family and I were delighted,” Begum said

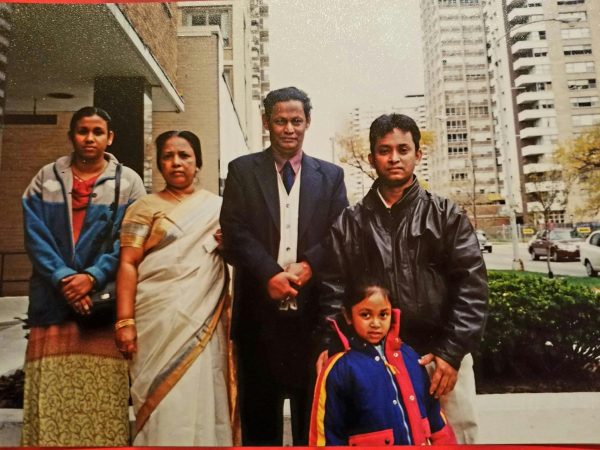

My mother immigrated to America after the birth of my oldest sister in 1997. They moved to an apartment near the lake. After some delay, my father got his degree in 2000, in computer science.

When I asked my father if he remembers any racially charged words or experiences he had, my father just shrugged and said there probably were some people calling him a “ terrorist or whatnot” after 9/11 but he doesn’t recall it.

“You learn to ignore it, because those people have the privilege to waste time spreading hate, while I have the privilege to ignore them,” Khan said.

He continued to work in the Renaissance until he chose to start managing a business for his friend, Ranki Khan, which is where he still works.

My parents then had my middle sister in 2005 and me in 2008. We have stayed connected to our culture by speaking the language at home, Bengali, going to Bangladesh, being a part of the Bangladesh Chicago Community, and most importantly by helping Bangladesh. My father encourages us to donate to boarding schools in Bangladesh that help underprivileged girls receive an education. Lastly, we embrace our culture by being a strong family unit.

His daughter, my sister Sabrina Nur, and Niles West Alummi thinks that his story echoes through her own life.

“My dad is such a strong person and his immigration is something that substantially shaped him as a person. His story has also influenced mine, I work so hard because of him. The reason I go above and beyond, is because he sacrificed so much for me and my sisters to have a better life in America,” Nur said.

Sabiha Nur • Jan 27, 2025 at 11:50 PM

this is a great read!

Sabrina • Jan 27, 2025 at 4:24 PM

Awesome!

Riddhima • Jan 25, 2025 at 8:54 PM

This is very well written!!

Veronica • Jan 25, 2025 at 8:52 PM

omg best story ever???