Ted Sutkis walks point with a 12-gauge shotgun. After he crosses a stream, he sees two Viet Cong sitting on a rock eating rice patties. They notice him, but he immediately shoots and kills them.

“You didn’t have time to think. It was more of a reaction. If you thought about shooting someone, you’d be dead,” recalls Sutkis, who served in the Vietnam War from August 1968 to August 1969.

He then searches their backpacks. In the backpacks, he finds a transistor radio that was set to the same frequency his company was using to communicate. He radios the company that the Viet Cong know their exact positioning. He suggests they change the frequency, essentially saving his company.

Also in the backpack, Sutkis finds a Viet Cong flag. The colonel wants it, but Sutkis forces him to make a deal: Bring the company warm food, beer, mail, clothes, ammunition, and a birthday cake for one of the company’s men; the flag will not turned over until the supplies arrive.

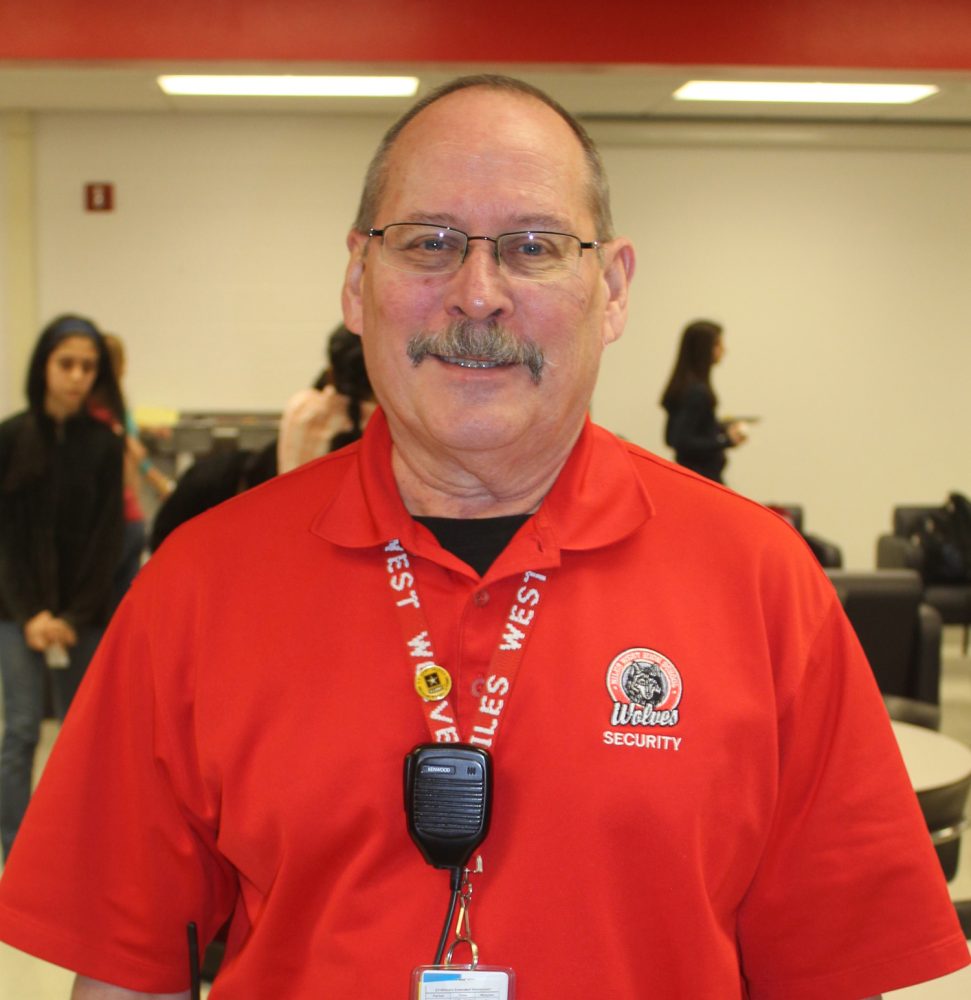

Sunday, Nov. 11 is Veterans Day when we honor those–like Sutkis–who have fought for America and celebrate their service. Sutkis, who now works as a security guard at West, said the experiences he faced in Vietnam are ones that he will never forget, especially his first day on the ground in Vietnam: Moving deceased soldiers is something that stays with you forever.

Just after his 18th birthday, Sutkis was drafted by the United States military. He was sent to Fort Poke, La. from Chicago for his basic training. Before he was to go to Vietnam, he expected to be able to go home to see his family. However, he was unable to because the military forced him stay there for his advanced training. After that, he was sent directly to the front lines. He was unable to see his family one more time before he left, and could only communicate by letter.

“I [was] not old enough to vote, not old enough to drink, but I was old enough to fight,” he said.

The flight to Vietnam was 24 hours. The plane made a stop in Guam, but then continued on to Cam Rahn Bay, located on the eastern coast of the country. He spent two days there before being transported to the Central Highlands to meet up with his company, The Fourth Infantry Unit. Sutkis reflects about the first job he did when he arrived for his short stay in Cam Rahn Bay.

“My first job when I arrived [in] Vietnam was to move dead soldiers into wooden caskets [that were] to be sent back to the US. That’s just something you don’t forget,” Sutkis said.

The Central Highlands was all jungle. It was hot (usually more than 100 degrees) and humid all the time. Six months out of the year, it rained. The soldiers didn’t just have to deal with the harsh weather conditions, but also leeches, snakes, and most importantly, the Viet Cong and their infamous booby traps.

The soldiers also couldn’t always take showers. Most of the time, they had to bathe in the river. Once, nearly half of Sutkis’s company was wiped out while they were bathing. At times like these, soldiers had to hope and pray that you made it home in one piece.

The water they drank was from the rice patties. It was so disgusting, they had to treat it for diseases and then pour Kool-Aid in it to get rid of the nasty flavor. The soldiers often got very little sleep. Usually three to four hours per night.

The harsh conditions caused the soldiers to age faster than usual. On the first day with his company, Sutkis met men who looked years older than him; when in reality, they were only a year older.

Not every day in Vietnam was a bad day, though. Some days, the soldiers didn’t fight. They just hung around. A lot of times, parents would send care packages full of food and things from home. Not all of the guys got care packages, but it was customary to share what you got. The saying “a good soldier never leaves a man behind” comes into play here. The company was with each other through thick and thin, and they all looked out for each other.

“For every bad day in Vietnam, I saw 10 good ones. Not every day was a bad day,” Sutkis said.

By August of 1969, Sutkis was wounded twice. He was finally able to come home to see his family for a short visit because he had to finish his tour in Fort Carson, Colo. He came out of Fort Carson as a sergeant and was awarded two purple hearts. His welcome home gift from the United States was $100.

Unfortunately, because the Vietnam War was very unpopular, returning soldiers were looked down on, Sutkis said. They were called baby killers, and it took a while for the general public to appreciate the sacrifice the soldiers made in Vietnam.

Sutkis could have left the country before he got drafted, but he said he could do it if his father did in WWII.

“I could have went to Canada to avoid the draft, but I couldn’t ever come back. My dad served in [the military] in WWII. He served four years. So one was good enough for me if [four] was good enough for him,” he said.