https://soundcloud.com/thea-gonzales-62040266/otfs-episode-1-with-sharon-pasia

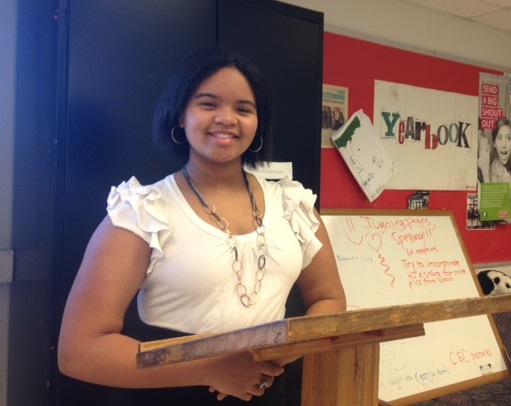

Listen to the very first episode of the podcast On the Flip Side discussing the representation of Asians in the media with Niles West alumna, working actor, and current student at the New York Film Academy in Los Angeles: Sharon Pasia.

I am an Asian woman. I also enjoy humor.

But the misrepresentation of Asians in the media stopped being funny a long time ago.

Earlier this April, I sat down and binge-watched the entire season two of Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt on Netflix. Yes, there are 13 episodes. Yes, I slept that night. I was enjoying myself, laughing uproariously at Titus’ antics, and spraying chips everywhere while attempting to sing along to the random songs that seemed to pop up in every episode. Needless to say, I loved the show.

And then came the arrival of Dong Nguyen, Kimmy’s main love interest and the show’s token Asian character. His behavior and characterization further raised some already-present questions that I had from season one: Why does he have to have such a thick accent and only speak in broken English? Why is Ki Hong Lee, a Korean-American actor, playing a Vietnamese character? Does he have to work as the delivery boy for a Chinese restaurant and be exceptional at math?

While watching Sisters with Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, I saw yet another Asian character whose main purpose was to gossip about the protagonists while doing their nails and bring Korean sex appeal to the party that the characters would later throw.

Suddenly, I was bombarded with images in the media that portrayed Asians as servile, willing-to-please characters who only speak in broken English, who are masters of martial arts or career-driven math geniuses who work so that they don’t “bring dishonor” to their families.

It’s getting old.

Asian characters in Hollywood are playing caricatures of entire nations of people who have rich cultures and deep histories that haven’t been respectfully — or even correctly — represented on screen for decades. Since 1915, a makeup technique called “yellow face” has been used to give white actors the facial characteristics of East Asians, which is extremely problematic for so many reasons. In light of Scarlett Johansson playing the originally Japanese character in the upcoming movie Ghost in the Shell, a Japanese manga, Vox recently published an article that explored the history of this misrepresentation and raised the question again: what is so wrong with having Asian actors play Asian characters?

This is not a new trend, but in 2016, I think we’re better than this. Sure, there is a far greater representation of cultures on screen than in the early 1900’s, but the problem has turned into how these cultures are being represented.

As an Asian woman, I am tired of seeing Long Duk Dong in Sixteen Candles and realizing that variations of the same mentality that existed in the 1980’s are still prevalent in film today: Chris Rock’s ironic joke about Asians at the #OscarsSoWhite Academy Awards ceremony, “Asian Reporter Tricia Takanawa” from Family Guy, and in so many other areas of the media.

Why can’t we have more London Tiptons or Joan Watsons or Montys or Nikitas or Dr. Cristina Yangs: dimensional characters played by Asian actors whose story lines don’t revolve around them trying to learn English or uphold the family honor?

Why does culture have to turn into a joke, and what is keeping people away from writing those kinds of characters or from casting Asian actors in roles with substance?

As a matter of fact, what’s keeping people from casting Asian actors in roles traditionally played by Caucasians?

When speaking about the move toward casting women in traditionally male roles, actress Natalie Dormer said, “If you just change the name of the character; that’s what Angelina Jolie did with Salt, which was a role originally for Tom Cruise. I think male writers maybe panic that they can’t write female characters too much. Just change John to Jane.”

Not only should we advocating for the inclusion of Asian actors in roles that aren’t traditionally Asian, but also roles that have no reason to be strictly Caucasian.

—

Some of you may be thinking, “She’s freaking out over nothing. It’s just a joke; it’s not that bad. It’s been like this forever, get over it.” I ask you: have you ever had to deal with being bombarded with images that depict your race as something to laugh at?

The effects of this subtle and historically offensive misrepresentation can have lasting impacts on the Asian community who begin to see themselves as less than what they are because of how the public is taught to see them.

“I had this acting teacher who was talking about women in film…he was saying how casting directors think — or used to think — and he said that if there was a tall, slender, busty, Caucasian, blond-haired, blue-eyed girl in the room and a five-foot-two, half Asian woman, the casting director would tend to look at the blond-haired, blue-eyed girl because that’s the look they’re looking for as a love interest. I am not slender. I am not light-skinned. I don’t have blond hair and blue eyes, and I’m five-foot-two. When I heard that, I sank into my chair, because…wow, does that mean that my looks are not capable of being seen as beautiful because I don’t look like that?” Pasia said.

It may be no big deal to see this misrepresentation when you don’t think about it, but what I’m trying to say is what you consume can consume you. This misrepresentation is disrespectful — whether intentional or not — and creates schemas of the Asian community that are hard to see past.

Niles West alumna, actor and student at the New York Film Academy in Los Angeles Julia Nejman has a unique perspective on the representation of Asians in the media as a mixed race actor, and she says that this subtle racism can be found everywhere.

“I am mixed race and considered racially ambiguous — on the industry side of things. If they ask, I say Filipino and Polish. It’s hard for me to fully identify as one or the other, but that’s just a matter of what I couldn’t control (i.e. my parents getting married and having me). I have yet to be cast as someone with a character description using ‘Asian girl,’ but I have experienced subtle racism on and off set. But who doesn’t? As sad as it is, I feel I’ve become numb to racial comments just because I know they’re not serious for the most part,” Nejman said. “As far as Asian actors in a film, I think it’s pretty clear that we’re in a white man’s world, nothing new. The industry is mostly lead by older white gentlemen, which I hope will eventually fade. Asians are usually cast as ‘nerds’ or ‘unattractive’ or anything along those lines. I think it’s a hard stereotype to break out of [but] it’s just a matter of being given the right opportunities.”

She also has advice for Asian actors hoping to go into the business and for regular viewers who can make a difference by challenging stereotypes on screen.

“It’s almost expected that anyone of color is going to be stuck in a stereotype at one point in their career. I think that Asian actors need to just show how diversely talented they are — stop settling for the roles you think are meant for the way you look. Take on roles that mean something to you — that don’t just require you knowing the answer to a math equation. Real, human, deep roles,” Nejman said. “As a viewer, just know that that person was most likely cast for the way they look, especially in the case of a stereotype. I think a big thing we can do is stop accepting the answers that have been given to us. Find our own.”

As a viewer, you can challenge yourself to see more than what you are fed through the screen. Question everything, think critically about what you are exposed to, and recognize misrepresentation for what it is, because even if it doesn’t affect you directly, what you consume can consume you.